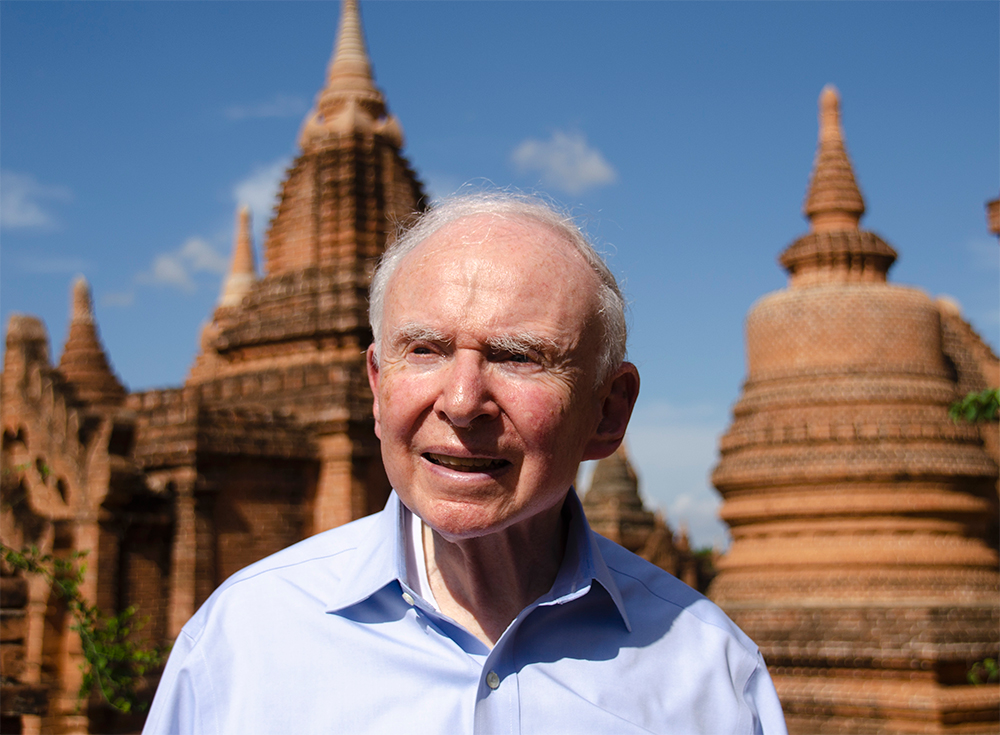

Roy L. Prosterman, a global development expert and activist whose pioneering vision and tireless advocacy for democratic, inclusive land rights reform impacted hundreds of millions of lives, died February 27 in Seattle. He was 89.

A corporate attorney turned University of Washington law professor and land rights champion, Prosterman’s work to address poverty and social inequity through land ownership has become a blueprint for improving lives and livelihoods in dozens of countries while stimulating broad-based economic development.

Over five decades, land rights reform programs guided by Prosterman and the global organization he founded, Landesa, have provided life-changing benefits to more than 700 million people. His model for systemic change drew the attention and praise of eminent leaders in international development, including Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz; Mary Robinson, former President of Ireland and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights; and the late Bill Gates, Sr., co-founder of the Gates Foundation.

It seemed an unlikely path for the young attorney, who accepted a position with the prestigious New York law firm Sullivan & Cromwell after receiving his law degree from Harvard Law School in 1958. But Prosterman would leave his rising Wall Street career behind in 1965, accepting a teaching post at the University of Washington. Led by a strong desire to alleviate suffering and conflict, he sought to find ways to use law to build more peaceful and prosperous societies. Drawing from experiences representing clients in Liberia and Puerto Rico, Prosterman came to appreciate the central role of land rights in shaping rural economies and building livelihoods.

At the same time, he recognized that the struggle over land was at the root of some of the 20th Century’s most violent conflicts—a trend he saw repeating itself as the war in Vietnam escalated in the 1960s. As the Viet Cong were recruiting thousands of impoverished tenant farmers desperate to feed their families, Prosterman was developing a bold, innovative legal solution to provide poor farmers secure rights to the land they farmed.

It was an idea that prompted action. Prosterman turned his ideas into a law review article titled “How to Have a Revolution without a Revolution”, in which he urged a democratic approach to making landownership more available to the masses, and particularly to those who depend on land for their livelihood. His article caught the attention of policymakers in the US. Before he knew it, the young lawyer in his early 30s was standing in a rice paddy amidst the Vietnam War, testing the idea through a South Vietnam government “Land to the Tiller” program. The program gave land rights to one million South Vietnamese farmers. The sweeping land reform was credited with increasing rice production by 30 percent while slashing Viet Cong recruitment by 80 percent. A New York Times article called the land reform law that Prosterman had authored “probably the most ambitious and progressive non-Communist land reform of the 20th century.”

Moreover, the groundbreaking program set precedent for land rights reform as a crucial intervention in reducing poverty and sparking sustainable development. After the war, the government land rights reform in Vietnam that Prosterman primarily authored set the groundwork for transforming collective farms in Northern Vietnam to family farms, leading to significant gains in both food productivity and household income. Today, Vietnam is one of the largest rice producers in the world. It is no exaggeration to say that Vietnam’s emergence as one of the “Tiger Cub” economies of Southeast Asia has its roots in the land rights reforms authored by Prosterman some five decades ago.

Founding the world’s first land rights NGO

Soon Prosterman found himself called into the fields of Latin America, the Philippines, Pakistan, and other countries to help craft pro-poor land law and reform programs. He developed a small following of law students who assisted him in his work, which through the early decades was conducted out of the University of Washington Law School.

From the 1960s through the 1980s, Prosterman’s work from the University of Washington included related efforts on nuclear arms reduction, world hunger, and foreign aid reform. Prosterman chaired a Conflict Studies initiative at the University of Washington, was instrumental in the 1977 founding of the global NGO Hunger Project (with John Denver and others), successfully worked with the US Congress to get legislation that targeted U.S. foreign aid on the worst poverty and suffering, and for many years conducted influential annual report cards of U.S. foreign aid.

Over the years, however, another idea was germinating that brought Prosterman back to a laser focus on land rights reform. In early 1992, Prosterman and long-time collaborator Tim Hanstad moved the operations out of the University of Washington into an independent non-profit organization, initially called Rural Development Institute and later renamed Landesa.

The approach Prosterman initially employed in Vietnam – using data-informed land law and policy as tools to empower historically marginalized populations — greatly expanded through Landesa. Over the years, Landesa has worked in more than 60 countries and helped governments provide secure, legal land rights to more than 700 million women and men, putting them on pathways out of poverty. Landesa’s impact has resulted in the organization being ranked among the Top 10 NGOs in the world, a ranking it has maintained for the past 12 years. Prosterman remained active with Landesa into his late 80s.

Even after Landesa was formed, Prosterman continued to teach at the University of Washington Law School, where he also founded and directed a graduate program in the Law of Sustainable International Development, which continues today. Along the way, he published several books, including Surviving to 3000: An Introduction to Lethal Conflict, Land Reform and Democratic Development (with Jeffrey Riedinger), and One Billion Rising (with Tim Hanstad and Robert Mitchell), and authored scores of articles and book chapters.

During his career, Prosterman received numerous awards and distinctions, including the Gleitsman Foundation International Activist Award, which honors achievement in alleviating world poverty, a Schwab Foundation Outstanding Social Entrepreneur Award, the Henry R. Kravis Prize in Leadership, and University of Chicago Alumnus of the Year. He was also nominated three times for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Roy L. Prosterman was born July 13, 1935, in Chicago, Illinois, to Sidney Prosterman, of Russia, and Natalie Weisberg-Prosterman, of Wisconsin. A fastidious student from early on, Roy attended South Shore High School where, at sixteen, he received a pre-induction scholarship from the Ford Foundation to attend the University of Chicago. He graduated with a B.A. in 1954 (at the age of 18) and completed his J.D. at Harvard Law School in 1958.

He was preceded in death by his parents. He is survived by the family of Tim and Chitra Hanstad and their children Rajan, Rani, Asha, and Shalini Hanstad, and by the 150 members of his Landesa team: land law and tenure experts, colleagues, and friends around the world, who together work to continue Prosterman’s legacy and vision in pursuit of peace and inclusive prosperity.

A celebration of life will be held on April 26 at 2pm at Seattle First Covenant Church (400 E Pike St, Seattle). Gifts in celebration of Roy and the continuation of his life’s work can be made to Landesa at landesa.org or by mail to the Landesa office at 1424 Fourth Avenue, Suite 430, Seattle, WA 98101.

Related news